A psychology professor was giving an oral test. Speaking about manic depression, she asked, “How would you explain a man screaming at the top of his lungs one minute, then sitting in a chair weeping uncontrollably the next?” An athlete in the third row offered, “Umm, maybe he’s a basketball coach?”

Ha ha… I thought I should start this off light. Though, you should bail now if you’re hoping for light-hearted entertainment.

I know… I haven’t been blogging. Or keeping in touch with anyone. Or writing much at all. Or being more than marginally productive. Or really even looking forward to the future.

I have been:

1) going through the motions

2) drinking regularly

3) putting on a good show

4) hoping I’ll feel better really soon

Oh, and traveling. And sometimes even writing down things I might blog about. But then not caring enough to actually start typing.

What happened? Long story. Or maybe… long hypothesis.

♦ ♦

My whole life, people have always asked me, “Where do you get your bottomless energy?!” And told me to lay off the coffee/drugs. And asked me what I was “on.”

Answer: I don’t know. I don’t know where I got my drive, motivation, positivity, and perma-happiness to be alive.

But it disappeared — swallowed whole by that strange, nebulous, dirty, ten-letter word — depression.

I tried to look up depression statistics for you. Too hard basket. We’ve all seen renderings of the data at some point. The take-away is that really-a-whole-lot-of-people suffer from depression at least once in their lives. What’s lame is that we don’t talk about it. (Which is why I am publishing this entry when I’d rather banish this skeleton to the back of my closet forever.)

Depression today is like the getting-a-divorce of the 60’s and 70’s. I think the lack of cultural definition around depression just serves to isolate and alienate depression sufferers who are already isolating and alienating themselves. Not only do they not want to talk about it… they aren’t supposed to. They shouldn’t. Depression is a social faux pas. Especially if it doesn’t stem from a traumatic event, like losing a loved one or returning from a war zone.

I think many sucked into the vacuum of depression, me included, feel like it isn’t “real” depression. We don’t want to kill ourselves yet, we can still accomplish basic tasks when they become completely unavoidable, and sometimes we even briefly get it together to do things that normal people are doing. Therefore, it’s not that bad. This sentiment is echoed by my favorite graphic-blogger, Allie Brosh (of Hyperbole-and-a-Half fame) who fell into depression for a over a year. When she finally came out of the fog, her first post explaining why she’d gone so long without sharing her comic genius with us starts out: “Some people have a legitimate reason to feel depressed, but not me.”

When you’ve never been depressed, I think it’s hard to confront depression in your loved ones. It has many of the same awkward overtones involved in grief and loss. “I’m sorry you’re depressed” seems just as empty and hollow as “I’m sorry about your loss.” These are situations without easy action plans and without silver linings.

Allie also notes, in a follow up post about her “Adventures in Depression”, that “It’s weird for people who still have feelings to be around depressed people. They try to help you have feelings again so things can go back to normal, and it’s frustrating for them when that doesn’t happen. From their perspective, it seems like there has got to be some untapped source of happiness within you that you’ve simply lost track of…”

While I’d been through bouts of extended ickiness in my life (who hasn’t?), I had never gone beyond “many bad emotions, theme: hopelessness” to “no emotions.” One common idea about depression equates it with sadness. This year I learned depression often means waking up and feeling… not sadness, but nothing. The beginning of this Allie Brosh gem explains it well, in terms we can all understand — the adventures of your childhood toys. Go. Read.

“Cognitively, you might know that different things are happening to you, but they don’t feel very different.”

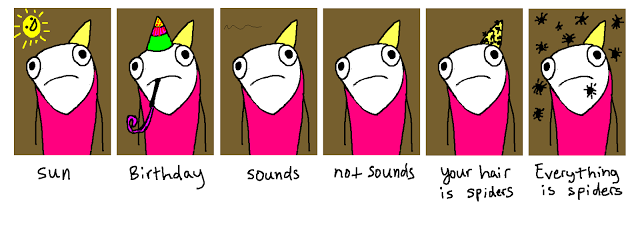

It seems to me putting depression on a scale might be handy. For the sake of empathy, I’ll scale intoxication instead — something most people can relate to.

There’s:

- I’ve had a beer.

- I’m feeling tipsy.

- I probably shouldn’t drive but am going to anyway.

- No! I’m totally fine to drive! I swear!

- I couldn’t drive if I tried.

- I couldn’t walk if I tried.

- Only if I’m very lucky will I have hazy memories of this.

- I am a unicorn.

- The line between me and death is razor-thin.

While you’ll struggle to find someone who’s never had a beer or felt tipsy, there are plenty of individuals who’ve never been blackout drunk. Or a unicorn. Or the victim of an alcohol-induced coma. Perhaps this is the reason depression can be so hard to understand. Possibly the lack of labels for the spectrum contributes to the silence and discomfort around the topic.

All the fuzzy, culturally undefined stages in between the equivalent of “being tipsy” and “being very near death” leave depression sufferers with no language. Not only is the topic taboo, but depressed folks don’t care enough or have enough hope to even want to say anything in the first place. Couple that with the self-deprecating sense that one’s depression is probably illegitimate, and things really start to snowball.

Turning Point

Probably the most shocking moment in my depression was when it dawned on me that I was successfully fooling everyone around me into believing I was basically still okay. With the help of my good buddy alcohol, I’d made it though another social evening. Later, as I reflected on how I hadn’t looked forward to it and was relieved when it was over, I had a new thought. “And I’m glad no one knew.”

Which led to more new thoughts: “Holy sh*t. There is nothing I’m looking forward to in life. Nothing. And no one knows. I mean surely they can tell that I’m not 100%. But I don’t think they know I’m not even 50%. I’m not even 25%. This is how it happens. This is how people take their own lives and then afterward all their friends and family say things like, ‘I never saw it coming. S/he seemed fine. We just had lunch last week. S/he seemed a little down, but nothing that bad.’ ”

I knew I wasn’t doing great, but really didn’t want to have to explain something I didn’t understand or to be confronted about the illegitimacy of my apathy.

While I had yet to contemplate suicide, realizing that I wasn’t getting better and that no one knew how disconnected-from-life I was scared me enough to want to take some kind of action.

Back in the early stages of my depression, when I still had bouts of caring about things and wanting to interact with people, when I still felt things (sadness, frustration, hopelessness), when I still wanted to talk about the bad things with hope of improving them, before the nothingness… I spent a long time trying to figure out why I’d felt so bad for so long.

My conclusion: I’d spent far too long not doing the things I care about or interacting with the people I care about.

See, I took this job in the middle of nowhere working way too much and having almost every minute of my day controlled by someone else. While I liked and enjoyed the actual job, the lifestyle ate away at me.

Aside from the complete lack of rejuvenating, non-work activities, my extreme isolation was probably the biggest factor. The very narrow windows of phone time I had didn’t line up at all with the social availability of my life-long loved ones. These are the folks who know me well enough to eagerly listen to bad things and help plot solutions. My isolation was further intensified by demographics and my choice to put myself in a socially-awkward situation in hopes of avoiding social ostracism.

Me at 6 a.m. – start of the work day, being told I’m too happy and have had too much coffee. On this day, and the 27 after, I did not: talk to my family or life-long friends, write, read, go on an adventure, play, veg, cook, etc.

Demographics? Yes. As a jack (jane?)-of-all-trades, I’ve spent my life floating between professional and blue collar worlds. But being able to fit in anywhere also kind of means there’s never anyplace I fit in fully. In both scenarios, at least half of my life experiences are different than my co-workers’, cutting auto-camaraderie in half.

The second hurdle to befriending my coworkers (and therefore lessening my isolation) was a combination of my unwillingness to lie and my unwillingness to be judged by anything but an individual’s personal experiences with me. I’ve explained before that my boyfriend was also my bosses’ boss, while I was a lemming. I refused to lie about the situation, but I also preferred that it wasn’t public knowledge. How could people who hadn’t gotten the chance to know me not suspect that I might spend the little time I had with my partner talking about what happened at work instead of anything-but-work? As a result, I avoided personal conversations with my workmates, unhappily eliminating the opportunity to be close to any of the people I spent 28 days at a time with.

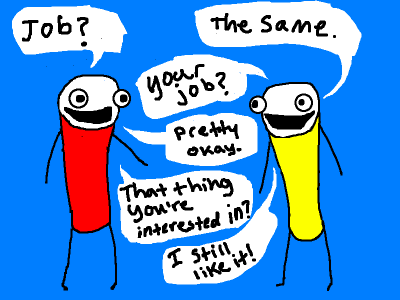

I was constantly forced into the lamest small talk ever thanks to the slightly-palatable small talk being off-limits… © the Amazing Allie Brosh

Oh those twenty-eight days. Even when they don’t involve my unfortunate brand of social isolation, twenty-eight days is still a long, long time to be away from friends and family, banks and grocery stores, your own bed and house, social gatherings and favorite escapes… “normal life.” Especially when — every time you leave all those things – it’s always for a whole month.

Not only are you gone for 28 days, but for the duration you have almost zero control over what you do with your time. There are no weekends off, no going home at night, no running errands or meeting friends on your lunch hour. There is just day after day of twelve-hour shifts and night after night in your allocated little cell.

In the morning before work, you have little choice but to get ready for work. In the evening after work, after taking care of your basic needs (showering, camp cafeteria dinner, laundry), you have maybe two hours to recuperate and fit in whatever other aspirations you may have for your life — if you can muster the energy. The lack of autonomy and change is soul-killing. If variety is the spice of life, this is cold stone soup.

It was particularly depressing to see the way the twenty-eight days affected my co-workers with families. I heard a story about a pre-schooler who thought the airport employed his dad because that’s the last place he saw him when it was time for Daddy to disappear again. Others told of sad family photos their children had drawn with their father off to the side, crossed out, or otherwise rejected. Another pre-schooler told his dad he wanted to “punch and kill [his dad’s workplace]”. One of my favorite workmates had a baby who didn’t even recognize him when he returned every 28 days. The guy got six days every five weeks to get to know his newborn/baby/toddler son.

It seemed to me that these guys (I worked with 98% men) were giving up time with their families in order to support said family. Inevitably, the time away took it’s toll. One month I listened to my neighbor fight with his wife on the phone every single night — and always about money. Lots of industry veterans had divorce scars. In the region where I worked, there were suicides about every 60 days – almost always married guys with kids. While the single guys seemed to fare better — experiencing the whole thing as more of a wild adventure — they still lamented missing out on “normal” life and found romantic relationships elusive. Who wants a partner you only get to see ten times a year?

So not only was I socially isolated with zero autonomy and no variety in my days (why does this sound a lot like prison?), I was also surrounded by people whose life situations made their daily highlight opening a cold beer at quitting time.

Umm… and… there’s more.

I’m an introvert. This is the proverbial straw that broke the straight-up killed my camel.

There are those who have confused my aforementioned enthusiasm with extroversion. However, I swear on my life… if I had to choose for the rest of my existence to be alone six days a week or be with people six days a week… alone. I pick alone. Alone, alone, alone, alone… what a beautiful word! I would even go as far as saying I need to be alone. I need it like a baby needs naps.

However, my job had the word “assistant” in the title — a word that requires the presence of another as part of its definition. Sure there were a few beautiful, blessed days where I got to fly solo, marinating in the 120 ºF metal storage container all by myself. But mostly I was “assisting.” Sometimes I got lucky, working one-on-one with a favorite work-mate. Introverts do well with 1:1, especially when that “1” is someone they really enjoy being with. Usually, however, my twelve-hour days were spent in a group (read: constant small-talk demands) of workmates also experiencing less than stellar lives (i.e. we all had a lot of nothing to talk about).

Maybe if I’d had the weekends to lock myself away and recharge my batteries, it would have been less of a problem. But weekends aren’t in the schedule. An RDO (rostered day off) is required every thirteen days, however. This means that in 28 days, two of them are spent doing whatever you want. Or at least whatever there is to do in a temporary camp in the middle of nowhere.

For most workers, the eve of this day off is an opportunity to get mind-eraser drunk. On my drinking scale above, that’s somewhere between I couldn’t drive if I tried and I am a unicorn. Despite desperately needing time alone, I often joined the party. I really liked several of my workmates. And making fun memories together would make all the other time we shared that much more enjoyable. I don’t regret joining the fun, but flushing that potential alone-time down the drain took its toll.

Don’t get me wrong. I wasn’t Miserable Molly from day one. Quite the opposite. I was having a blast. Lots of new and interesting things and people. I was constantly scribbling down notes that made their way into this, this, and this entry. At Halloween, I was excited to share a little slice of American culture. I happily gave up one of my six precious days away from site to bake a smorgasbord of treats for my hundred-plus co-workers.

But as my desperation to make up for the fun squeezed out by 84-hour work weeks increased, I increasingly packed every minute away from work — both at site and at home — with plans and goals and activities. Recuperation and alone-time got lost in the mix. By Thanksgiving, I was a humorless shell. By Christmas, I was lying on the floor of an empty bedroom crying. But I thought everything would be okay eventually. I’d bounce back as soon as the job ended.

“Plans are one thing,” wrote Tom Robbins, “and fate another.” Indeed. The plan, when my job ended, was to spend the last month of my Australian visa at home, alone, recuperating, recovering, and becoming human again. The fate was two-fold. 1) Instead of just vegging out and allowing myself the luxury of nothingness and alone-time, I suffered from intense FOMO (fear of missing out). As a result, I tried to squeeze in all the things I would have done had I not been working 84-hours a week for six months. I put off vegging out. “Later,” I thought. “Thailand, hopefully.” 2) The company my partner still worked for went bankrupt and rendered him ready-to-play several weeks earlier than planned.

Before I knew it, it was time to begin a travel adventure I’d organized long before my personality had started to atrophy. Singapore, Thailand, Germany, Spain, Sweden, America… all I had to do was get on a plane. Well, seven. The dominoes were ready to do their thing. So I let the current of life drag me along, trying desperately to carve out a few days of “me” time here and there. Each time I made my way to the eye of my growing depression-storm, I hoped it would be the magic bullet that would finally set me right again. I was like a person who had gotten grievously ill but just kept going to work, hanging out with friends, going on already planned adventures… and then wondering why they never fully recovered.

Each time my woefully inadequate recuperation block failed to deliver a panacea, I lost a fraction more hope that I’d ever truly be myself again. Eventually, (red flag!) I just stopped caring. I stopped wanting to try to “get better.” It obviously wasn’t happening. The cycle of hope and disappointment took its toll. I let go. I had gone from occasional bouts of hopefulness where I’d tackle an overwhelming pile of unmade phone calls, unwritten emails, and overdue life responsibilities, to complete apathy. I had zero desire to talk to anyone or do anything. I just went with the flow of whatever was happening around me, unconsciously calculating the minimum amount of emotional effort necessary to make people think I was okay.

I knew for a long time that I had given up. But when it dawned on me that I was actively hiding that fact from everyone while seeing “things getting better” as only a very abstract possibility – like becoming an astronaut — that I was firmly on my way to becoming a statistic.

I suddenly recognized continuing to go through the motions was a disaster waiting to happen. Unlike some unlucky depression suffers, I felt mine sort of had a source: basically my failure to recover from the trifecta of not having enough alone-time, not having time to do things I enjoy, and not being in touch with loved ones.

I talked to my partner, who was as understanding as one can be when you’re powerless to fix something. I began searching for a quiet, furnished apartment where I could stop going through the motions, rebuild my introvert-me-time reserves, and hopefully start wanting to do things and talk to people again.

So here I am. Look! I wrote a blog entry! I called some people!

Am I out of the woods? Well, no. Not yet.

On the “if-depression-were-intoxication” scale, I’m probably still down at “No! I’m totally fine to drive! I swear!” But I feel like I’m sobering up. Slowly coming back to life. I have hope. I am definitely no longer a unicorn. ♣

Update: I am now fine. Part of me really wants to take down this blog post – the same part of me that never wanted to write it in the first place. But maybe someone who needs help will read it in a depression-fueled internet binge and recognize some of my depression-addled thoughts in themselves and be inspired to get help… in which case leaving my little tome in cringe-worthy public view seems like a pretty small sacrifice.

Update #2: I am even finer, after doing some very heavy thinking two-and-a-half years later. I’ve concluded that there is a very strong connection between a sense of identity and motivation. I believe a loss of autonomy sets the stage for depression. Probably some people with psychology degrees already know this, but here’s my lay-person’s explanation and my recovery action-plan that is finally working splendidly.

4 pings